Global human population is currently at approximately 7.5 billion people and increasing by about 1.1% per year. However, the rate of growth of the population growth rate itself is decreasing so world population is expected to level off somewhere near 10-11 billion people around the year 2100. This leveling-off is encouraging from a sustainability perspective but an extra 3 billion people is still quite a bit for the earth system to support.

Since everything humans do requires energy and since our energy system still largely relies on fossil-fuels, the number of people on the planet has a large effect on projections of the impact of global warming. This is why having ‘one fewer child’ has been noted as the single most significant lifestyle decision people can make in terms of reducing their carbon footprint.

This raises a couple questions:

1) How much worse do we expect climate change impacts to be due to this 3 billion-person increase in population?

2) How much faster would we have to ‘decarbonize’ society in order to offset the impact of adding these 3 billion people?

We can get first-order answers to questions like these using the type of simplified equations that go into ‘Integrated Assessment Models’ like the Dynamic Integrated model of Climate and the Economy. In these simplified models of the environment and society, the impact of climate change is quantified by the ‘damage function’ which expresses the damage caused by global warming in terms of a fraction of global gross domestic product (GDP). (The damage function is extremely uncertain but its estimates are becoming more empirical).

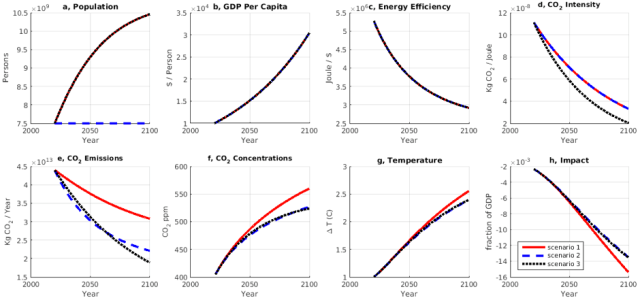

Using this framework, we can compare the climate change impacts in a world where population grows from 7.5 billion to 10.5 billion by 2100 (scenario 1, red line below) to a scenario where global population stays steady (scenario 2, blue dashed line below). In these situations, I am considering a middle-of-the-road projection where CO2 emissions continuously drop (panel e) but not fast enough to keep up with the ambitious goals of the Paris Accord.

Comparing the population (panel a) and the climate change impact (panel h), we can see that the additional 3 billion people increases the negative impact of climate change from approximately 1.3% of GDP (blue dashed in panel h) to 1.5% of GDP (red line in panel h) in 2100. This doesn’t seem like a huge difference, meaning that offsetting this difference might not be an insurmountable challenge. So what else could we change in order to offset this additional 0.2% of GDP damages?

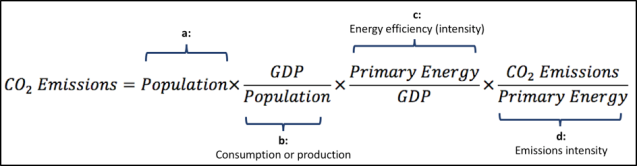

We hear about several possible ways that society could go about decarbonizing; from consuming less, to increasing energy efficiency, to transitioning from fossil fuel to renewable energy sources. In fact, along with changes in population, these things represent all the possible avenues by which humanity can reduce carbon dioxide emissions. These features are described quantitatively with the Kaya Identity which breaks down carbon dioxide emissions as:

The four terms of the Kaya Identity are plotted in the first four panels above (panels a-d).

This tells us that in order to offset the climate change impact of the 3 billion-person increase in population (a) we need to have either a smaller increase in consumption (b), a larger decrease in energy intensity (c), or a larger decrease in the amount of CO2 we emit per unit of energy (d).

Globally, material consumption – and its flip side production (b) – have been increasing by about 1.4%/year and is expected to continue to grow at a growing rate over the remainder of the century. Energy efficiency (c) has been increasing (or energy intensity has been decreasing) by about 1-2%/year and apparently, this is expected to continue until at least 2040. The carbon intensity of energy (d) – transitioning from fossil fuel to renewable energy sources – is where most policy discussions center and thus I will single-out that term here.

As the baseline, I have assumed that carbon intensity of energy will decrease by 1.5%/year, which is a middle-of-the-road estimate. So the question becomes, how much more of a decrease in carbon intensity do we need in order to offset the increase in population?

The black dashed line (scenario 3) illustrates how this can be achieved. It shows that, in order to have the same impact (panel h), carbon emissions intensity would need to shift from a growth rate of -1.5%/year to -2.1%/year. So, from a climate perspective, the impact of the additional 3 billion people can be offset by what seems like a relatively modest change in the rate of decrease in carbon emissions intensity. Hopefully, this is not an illusion and this level of decarbonization of the energy system proves to be both technologically and politically feasible.

Pingback: Week in review – science and policy edition | Climate Etc.

Given a population projection what is your assumption of carbon footprint per person?

Pingback: Dear Humanity - Optimizing America

Pingback: Dear Humanity – Are you seeing what’s happening? - Jarljensen